How eSource Technology Ensures High-Fidelity, Consumable Data

Sponsors considering using data from sensors and wearables in their clinical trials worry about three scenarios: collecting too little data, collecting too much data, and collecting bad data.

Each outcome could likely impact their study or a portion of it with a significant waste of time, money, and patient goodwill.

How can you de-risk the use of directly captured data from patients? How can you ensure that incoming data is properly ingested, stored, consumed, and managed to avoid potential issues?

Consider the specialized expertise required to integrate the right data collection application—a unified data platform—and the most advanced analytical methodologies.

Here is some insight from the Clinical ink Advanced Technology Team:

Solving “Too Little Data”

Sponsors may end up with too little data and insufficient statistical power when a protocol is too taxing for patients. Recruitment falters and adherence drops off. Getting expert consultation on protocol design provides an early and thorough assessment of all the abilities and limitations of the target patient profile.

Understanding patient insights and the use of patient-centered measures and assessments guides the technology strategy that will help prevent situations leading to “too little data.”

Clinical ink on Solving “Too Little Data”

In one assessment, recommendation against requiring prospective participants to complete a nearly 100-question survey at the start of the study could prevent loss of participation.

Evaluation concluded the process represented a burden that the particular patient population may not overcome.

Managing “Too Much Data”

Can you ever really have too much data? Maybe not, but wearables and sensors generate colossal and continuous streams of data. You can have more data than a particular system can handle or analysts can interpret.

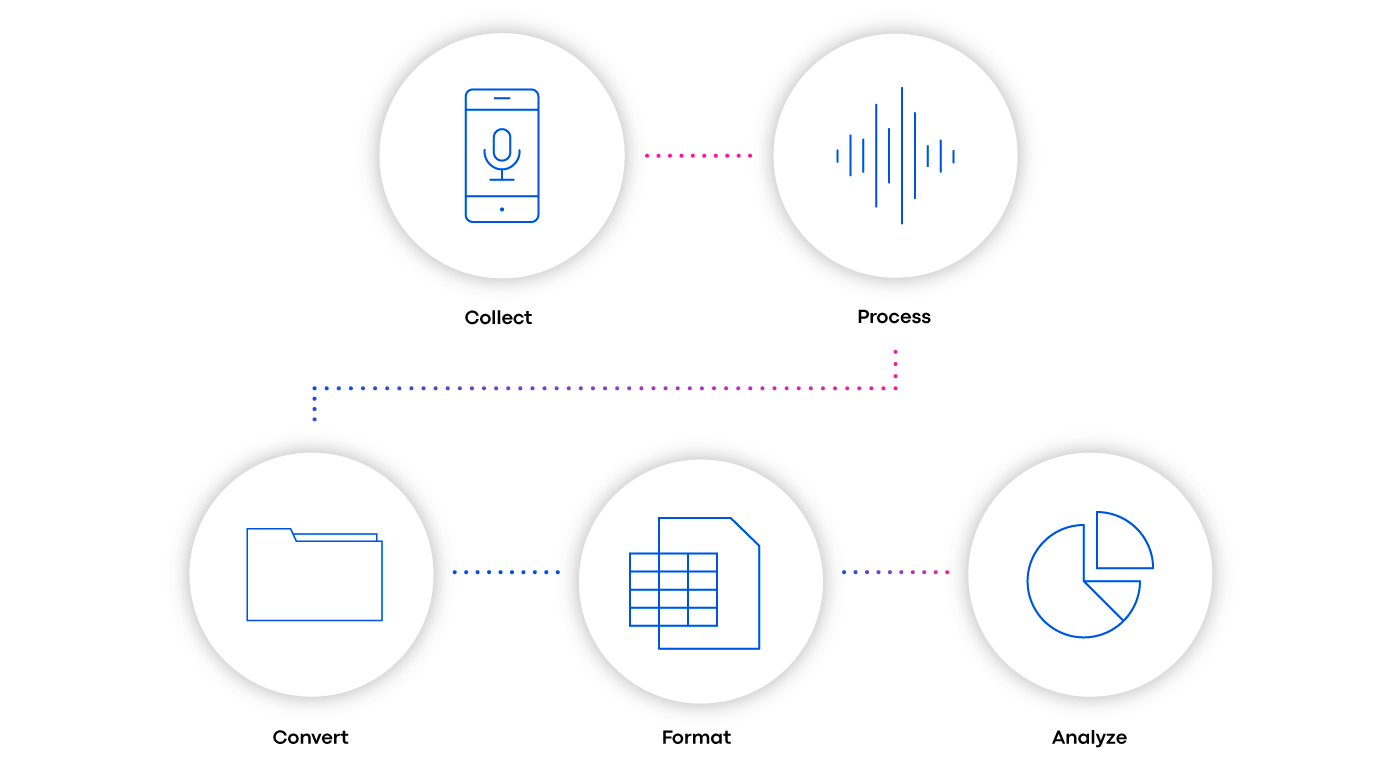

The Clinical ink solution involves using a data platform that can store, process, and analyze any type and volume of data associated such as patient cognition, mobility, and phonation. Technology led by an expert analyst team converts incoming raw data into file formats — and ultimately dashboards — that Sponsors can easily consume (See Fig. 1).

Clinical ink on Managing “Too Much Data”

For instance, one assessment used in studies in Parkinson’s disease and COVID is a verbal phonation exercise in which the patient is asked to sustain a certain sound (such as “ah”). The incoming data is binary — a series of ones and zeros — and readable only by machines.

Converted into human-readable files that contain variables enables data scientists to screen important data for analysis. Getting reports and visualizations for data analysts to query the data is crucial in detecting signal patterns and drawing conclusions.

Preventing “Poor Quality Data”

Ensuring that the data collected from sensors and wearables is clean and usable requires a deep understanding of the therapeutic area, a detailed knowledge of industry standards, cutting-edge research analytical practices, and a patient-centered approach.

To ensure that collected data is of the highest integrity, here are few rules:

-

- Rely on applications and tools that have been evaluated for that specific research purpose. In any therapy area, leverage industry standards and consult with experienced research leaders to determine what signals will be most meaningful.

- Rely on applications and tools that have been evaluated for that specific research purpose. In any therapy area, leverage industry standards and consult with experienced research leaders to determine what signals will be most meaningful.

-

- Apply patient science, using qualitative and quantitative data collection methods, to ensure that the research approach is centered around the patient rather than the technology.

- Apply patient science, using qualitative and quantitative data collection methods, to ensure that the research approach is centered around the patient rather than the technology.

-

- Design applications to create an excellent user experience that encourages adherence to the protocol and minimizes the opportunity for “user error.”

- Design applications to create an excellent user experience that encourages adherence to the protocol and minimizes the opportunity for “user error.”

-

- Clean and filter data, at the individual patient level, to maximize usability and efficacy for data analysis and modeling.

- Clean and filter data, at the individual patient level, to maximize usability and efficacy for data analysis and modeling.

-

- Consult your own quality control dashboards as data points come in and at the conclusion of studies to continuously improve methodologies.

- Consult your own quality control dashboards as data points come in and at the conclusion of studies to continuously improve methodologies.

Concerns over volume and quality of data generated in a trial are natural and should always be discussed as potential risks. Consider overcoming these challenges as fundamental to the success of any study — particularly those using eSource and more complex streams of patient data gathered from sensors and wearables.

To learn more about how Advanced Technology Teams in our industry operate, and how they prepare some of the most complex datasets for analysis, read “Debunking Complex Data Preparation and Analysis.”

Author

Anna Keil

Senior Software Engineer, Clinical ink